PMPRB Guidelines Modernization – Discussion Paper – June 2016

Rethinking the Guidelines Phase 1 public comments now available!

Phase 1 of Rethinking the Guidelines closed on October 31, 2016. Visit the Rethinking the Guidelines section to view the submissions we received on this Discussion Paper and for more information on the next steps in this consultation process.

ISBN: 978-0-660-05293-9

Catalogue number: H82-21/2016E-PDF

June 2016

PDF - 3.19 MB

Vision

A sustainable pharmaceutical system where payers have the information they need to make smart reimbursement choices and Canadians have access to patented medicines at affordable prices.

Mission Statement

We are a respected public agency that makes a unique and valued contribution to sustainable spending on pharmaceuticals in Canada by:

- Providing stakeholders with price, cost and utilization information to help them make timely and knowledgeable medicine pricing, purchasing and reimbursement decisions

- Acting as an effective check on the patent rights of pharmaceutical manufacturers through the responsible and efficient use of its consumer protection powers.

Motto

Protect, Empower, Adapt

Disclaimer

This paper is for discussion purposes only, to obtain public and stakeholder feedback on the need for reform and the nature and scope of potential changes to the Guidelines. It is not intended as a definitive articulation of the PMPRB’s position on these issues.

Message from the Chairperson

It has often been said that the PMPRB was conceived as the consumer protection “pillar” of its originating legislation, Bill C-22. That legislation was contentious at the time, and the credibility and effectiveness of the PMPRB as a regulator was seen as key to ensuring the long-term viability of the policy compromise embodied within the Bill. However, with Canadian patented drug prices outpacing most of our comparators and OECD partners, record low investment in pharmaceutical R&D, and public and private payers struggling to cope with an influx of high-cost drugs, many are questioning the effectiveness of the PMPRB in meeting the government’s policy objectives. As we embark on our journey toward reform and renewal described in our Strategic Plan 2015-2018, we are consulting on potential changes to PMPRB Guidelines, as mandated by section 96(5) of the Patent Act, that will enable us to better deliver on these policy objectives. As this process unfolds, we look forward to working with all of our stakeholders in realising our vision of a sustainable pharmaceutical system where payers have the information they need to make smart reimbursement choices and Canadians can afford the patented drugs they need to live healthy and productive lives.

Executive Summary

Recent and significant changes in the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board’s (PMPRB) operating environment necessitate corresponding changes to modernize and simplify its regulatory framework. As a first step in this process, the PMPRB is undertaking public consultations to obtain submissions from stakeholders and the public regarding possible reform of its Compendium of Policies, Guidelines and Procedures (Guidelines). The public consultation process is an invitation for all interested parties to collectively rethink the Guidelines to ensure they remain relevant and effective in enabling the PMPRB to protect consumers from excessive prices in a dynamic and evolving pharmaceutical market.

This discussion paper provides a framework for consultations by identifying aspects of the Guidelines that appear to be particularly outdated and asking a series of broadly formulated questions intended to inform the second phase of the consultation process when specific changes to the Guidelines will be proposed based on the feedback received to the questions. While the PMPRB is committed to reforming its Guidelines, it has no preconceptions about the specific changes that may result from this process.

Consultations on the discussion paper are meant as a platform for stakeholders and the public to engage in an open, frank and transparent exchange of views and ideas on the nature and scope of Guidelines reform. Any feedback that falls outside these parameters will be referred to the appropriate authorities for their consideration.

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to give effect to the PMPRB’s obligations under section 96(5) of the Patent Act by consulting stakeholders and interested members of the public on changes which could be made to the PMPRB’s policies, guidelines, procedures and regulatory enforcement approach. The title of the paper, PMPRB Guidelines Modernization, reflects the PMPRB’s intent to take a fresh look at how it protects consumers from excessively priced patented medicines based on the factors in section 85 of the Patent Act.

The paper has the following objectives:

- stimulate an informed discussion on the changes that have taken place in the PMPRB’s operating environment;

- identify areas of the Guidelines that may be particularly in need of reform in light of these changes;

- encourage public participation to obtain a diverse array of viewpoints on the direction of Guidelines reform;

- support the PMPRB in its continuing efforts to protect consumers from excessively priced patented medicines.

Introduction

Who are we?

The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) is an independent quasi-judicial body established by Parliament under the Patent Act (“Act”). Although part of the Health Portfolio, due to its quasi-judicial responsibilities the PMPRB carries out its mandate at arm’s length from the Minister of Health (who is nonetheless responsible for the sections of the Act pertaining to the PMPRB). The PMPRB also operates independently of Health Canada, which approves medicines for safety and efficacy; other Health Portfolio members, such as the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canadian Institute for Health Research; and provincial drug plans, which approve the listing of medicines on their respective formularies for reimbursement purposes. Under the Whole-of-Government framework, the PMPRB’s program activities are aligned with the high-level outcome of a responsible, accessible and sustainable health system.

The PMPRB was created in 1987 as part of a major overhaul of Canada’s drug patent regime, which sought to balance potentially competing policy objectives. On the one hand, the government strengthened patent protection for drugs in an effort to encourage more pharmaceutical industry research and development (R&D) investment in Canada. On the other, it sought to mitigate the financial impact of that change on Canadians by creating the PMPRB. The PMPRB was described as the consumer protection pillar of Bill C-22. That description has been endorsed on multiple occasions by the courts, including by the Supreme Court of Canada in 2011. The stated purpose of the PMPRB was to ensure that patentees did not abuse their newly strengthened patent rights by charging consumers excessive prices during the statutory monopoly period.

At the time Bill C-22 was enacted, policy makers believed that patent protection and price were key drivers of pharmaceutical R&D investment. The choice was thus made to offer a comparable level of patent protection and pricing for drugs as exists in countries with a strong pharmaceutical industry presence, on the assumption that Canada would come to enjoy comparable levels of R&D. In exchange for amendments to the Act which strengthened drug patent protection, Canada’s Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies (recently rebranded as “Innovative Medicines Canada” or “IMC”) committed to double R&D output in Canada to 10% of sales.Footnote 1

Why are we consulting?

The impact of the policy over time has been the opposite of what was intended. Canadian patented drug prices have been steadily rising relative to prices in the seven countries to which Canada compares itself under its regulations (France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the US – the “PMPRB7”) and are now third highest, behind only Germany and the US. Since 2000, Canada’s growth in patented drug expenditures as a share of GDP has increased by 184%, outpacing all the PMPRB7 countries over that period. Outside of the PMPRB7, prices in Australia, Austria, Spain, Finland, the Netherlands and New Zealand are between 14% and 34% lower than Canadian prices. Looking beyond just patented drugs to all prescription drugs, Canada spends more per capita and as a percentage of GDP than most other countries.

As prices in Canada rise, R&D investment is declining. Since 2003, IMC members have failed to meet their 10% commitment and the current ratio stands at 5% of sales. This is the lowest recorded ratio since 1988, when the PMPRB first began reporting on R&D. In contrast, the average R&D ratio of the PMPRB7 countries has held steady at above 20%.

The coupling of high Canadian patented drug prices and record low investment in R&D has many questioning the effectiveness of the PMPRB in meeting the government’s 1987 policy objectives. This viewpoint was echoed recently by the Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation in its July 17, 2015 report Unleashing Innovation: Excellent Healthcare for Canada, which concluded that the PMPRB needs to be “strengthened” to better “protect consumers from high patented drug prices.” These same concerns are what prompted the PMPRB to undertake a year-long strategic planning process, the results of which seek to reaffirm the organization as an effective check on the patent rights of pharmaceutical manufacturers and a valued source of market intelligence for policy makers and payers. The former of these two objectives will require adjustments to the PMPRB’s legal framework. These adjustments are consonant with and complementary to the ongoing efforts of the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Ministers of Health to “reduce pharmaceutical prices” while “enhancing the affordability, accessibility and appropriate use of prescription drugs.”Footnote 2

What are we doing?

At this initial stage of consultation, the PMPRB is seeking general feedback, in the form of responses to a series of broadly framed questions, on issues which will ultimately shape the second stage of consultations when stakeholders will be asked to comment on the technical modalities of Guidelines change. Throughout the process, stakeholders and members of the public who wish to submit their views are respectfully requested to give due consideration to the PMPRB’s consumer protection mandate, the Supreme Court’s interpretation of its purpose, issues of affordability, price transparency, domestic and international price differentials, R&D trends, regulatory burden and international best practices.

The consultation process will involve three distinct phases to ensure that stakeholders and the public have ample opportunity to voice their concerns and perspectives, in keeping with both the letter and spirit of section 96(5) of the Act.

| Phase |

Steps |

Proposed Timelines |

| Phase 1: Consult with Stakeholders on Issues |

Publish Discussion Paper

Meet with various stakeholder groups across Canada

Obtain written comments from stakeholders and the public on questions in the discussion paper

Gather and analyze all results from Phase 1 of consultation |

Summer/Fall 2016 |

| Phase 2: Engage Stakeholders and Gather Expert Input |

Public Policy Hearing – invite stakeholders to appear before the Board and make representations in support of their written submissions |

Fall 2016/Winter 2017 |

| Phase 3: Presentation of Proposed Changes |

Publication of proposed changes to Guidelines for comment through Notice and Comment Process

Strike multi-stakeholder forum(s) on specific issues and proposed changes to the Guidelines |

Spring/Summer 2017 |

The PMPRB would like to hear from as many people as possible and will consult nationally with a wide range of stakeholders, including:

- consumers and patient groups

- industry and industry associations

- public and private drug plan managers

- academia

- health care professionals and associated bodies

- health technology assessment agencies

- federal, provincial and territorial health ministries

- other federal government departments

- international partners

The PMPRB’s Regulatory Framework

The PMPRB’s legal authority is derived from the Patent Act (“Act”) and the Patented Medicines Regulations (“Regulations”). The Compendium of Policies, Guidelines and Procedures (“Guidelines”) represents non-binding interpretive guidance and direction from the Board to patentees and Board Staff on how to comply with the Act and the Regulations.

The Act

The Act as a whole falls under the jurisdiction of the Minister of Industry, with the exception of sections 79 to 103 pertaining to the PMPRB, which are the responsibility of the Minister of Health. These sections of the Act require that the PMPRB take remedial action when, following a public hearing, it finds that the manufacturer of a patented medicine is charging an excessive price. Subsection 85(1) of the Act identifies factors (“the section 85(1) factors”) that the PMPRB must take into consideration when evaluating whether a price is excessive. These are:

- the prices at which the same medicine has been sold in the relevant market;

- the prices at which other medicines in the same therapeutic class have been sold in the relevant market;

- the prices at which the medicine and other medicines in the same therapeutic class have been sold in countries other than Canada;

- changes in the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”); and

- other factors as may be specified in any regulation made for the purpose of this subsection.

If after considering the above factors in a hearing, a panel of Board members is unable to determine if a price is excessive, subsection 85(2) of the Act provides that it may consider the costs of making and marketing the medicine, as well as other factors which can be specified by regulations under that subsection, or that the Board members consider relevant in the circumstances.

The Regulations

The Regulations specify the information and documents that patentees must provide the PMPRB for it to carry out its regulatory mandate effectively. They include requirements relating to the prices of all patented medicines sold in Canada and prices in foreign countries where they are also sold. The Regulations also specify which countries Canada looks to in comparing its prices. Currently these are the seven countries of the PMPRB7, which, as mentioned, were selected on the basis of their level of pharmaceutical R&D.

Although section 85 of the Act allows for further excessive pricing factors to be prescribed in the Regulations or considered by Board members in a hearing context, no such guidance has been forthcoming to date. Under section 101 of the Act, only the Governor in Council has authority to make and amend the Regulations, subject to the recommendation of the Minister of Health on certain key matters. However, the Minister can only make such a recommendation after having consulted with provincial Ministers of Health, representatives of the pharmaceutical industry and other relevant stakeholders.

The Guidelines

Section 85 of the Act contemplates intervention only where a patented drug price is considered “excessive”, which is determined based on a set of broadly expressed factors. Given the open-ended nature of the exercise contemplated under the legislation, many of the core administrative concepts which give effect to the PMPRB’s consumer protection mandate have been developed through the Guidelines, which the Board is authorized to make under subsection 96(4) of the Act, subject to consulting first with relevant stakeholders.

While the Guidelines, by definition, do not have force of law, they have been held by the Federal Court to be useful both for the PMPRB and the public and may legitimately inform the Board’s reasoning in an excessive price hearing.Footnote 3

Under current PMPRB Guidelines, new patented medicines are assigned a ceiling price based on their degree of therapeutic benefit relative to existing drugs, as determined by a panel of scientific experts. Once a drug’s introductory ceiling price is set and it enters the market, the Guidelines allow annual price increases in keeping with CPI, provided these increases do not result in the Canadian price becoming higher than the price of the same drug in all of the PMPRB7 countries.

The purpose of the Guidelines is to ensure that patentees are aware of the policies and procedures normally undertaken in the scientific and price review processes in Staff’s determination of whether a price appears to be excessive. The Guidelines are important to the everyday function of the PMPRB, in that:

- they establish baseline principles for the fair, consistent and predictable application of the Act;

- they encourage voluntary compliance by providing patentees with sufficient understanding of the regulatory requirements to set prices at levels that are unlikely to trigger an investigation; and,

- they promote coherent administrative decision making.

In the event of non-compliance with the Guidelines, PMPRB Staff may refer the investigation to the Chairperson who must decide whether it is in the public interest to hold a hearing to determine if the price of the patented medicine is in fact excessive. Where such a hearing is commenced, the Guidelines may form part of the Board Members’ assessment of the issue of excessive pricing, to the extent that they represent a reasonable application of the Act, and the section 85 factors in particular, to the facts of the case, but are ultimately not binding on either the Board or the patentee.

While the factors in the Act are immutable (save amendment by Parliament), their open-ended nature allows for a flexible and contextually driven interpretation of excessive pricing under the Guidelines that evolves with time and changing circumstances. To that point, the current Guidelines remain grounded in a decades-old understanding of the Canadian and global pharmaceutical sector, as will be explained below. Guidelines modernization is a necessary first step toward bringing the PMPRB’s overall legal framework in line with today’s pharmaceutical environment and international best practices.

Changes in the PMPRB’s Regulatory Environment

At the time of the PMPRB’s creation, little was known about the relationship between price, intellectual property (IP) protection and R&D investment. Efforts by public and private payers to control prescription drug costs were in their relative infancy, including the concept of “international reference pricing” (i.e. benchmarking prices in one country to prices in other countries). Industry R&D efforts were focused on bringing medicines to market which treated the most common diseases and conditions, such as high cholesterol, high blood pressure and depression, and which were generally priced within reach of consumers and payers. Official “list” prices for medicines approximated the true price paid in the market and did not vary significantly between different types of payers (e.g. public vs. private). Finally, the government believed pharmaceutical companies would generally seek to avoid abusing their newly strengthened patent rights out of consideration for the political capital that had been spent securing passage of the underlying legislation.

In contrast, today, the empirical evidence does not support the idea that price and IP are particularly effective policy levers for attracting pharmaceutical R&D. Other factors, such as head office location, clinical trials infrastructure and scientific clusters, appear to be much more influential determinants of where pharmaceutical investment takes place in a global economy. Confidential discounts off the list price have become the industry standard, frustrating international efforts to contain pharmaceutical spending based on public list prices, and enabling companies to discriminate between different payers based on perceptions of the other side’s negotiating power and ability to pay. In Canada, this is resulting in a growing price gap between public payers, who are able to negotiate collectively through the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance (pCPA), private payers, who may lack the flexibility to do so under competition laws, and cash customers, who have no ability to negotiate. In countries where prices are determined at a national level for the entire population, this phenomenon is obviously less pronounced. In terms of industry focus, the era of mass-marketed, so-called “blockbuster” medicines has evolved towards one where the most profitable return on investment is made from very high-cost specialty medicines. These “nichebusters”, as the most successful are often called, target less common, untreated, and severe illnesses and conditions, but at a price even the most well-funded payers struggle to afford. Finally, the position of the Canadian pharmaceutical industry today is that any obligations arising from reforms brought in the late 1980s and early 1990s must account for the passage of time and the fact that many of those changes have since become entrenched as minimal norms and standards under bilateral and multilateral trade agreements (e.g. NAFTA and WTO-TRIPs).

The present-day reality is that the only meaningful constraints on what pharmaceutical companies can charge for their products is what the market will bear or regulators can effectively impose. In circumstances where a company holds a monopoly over the only treatment option for a particular disease or condition, payers sometimes have no choice but to pay the asking price, no matter how exorbitant. While the system may be able to absorb one, two, or even dozens of extremely high-priced new medicines, it is at risk of collapsing under the burden of hundreds, no matter how therapeutically beneficial or conventionally “cost-effective” they may be. Growing concern over sustainability has led other countries with public health care systems to introduce measures to address affordability issues, maximize value for money and keep pace with a rapidly evolving pharmaceutical market.Footnote 4

Guidelines Modernization

Although revisions to the Guidelines have taken place as recently as 2010, their general approach to applying the section 85 factors has not changed significantly since 1993. The following deconstruction of some of the key elements of that approach highlights aspects of the Guidelines that may be in particular need of reform.

Therapeutic benefit

The rationale for categorizing new patented drugs based on perceived therapeutic benefit is to attempt to align price ceilings with innovation. In other words, the better the medicine, the more a patentee should be allowed to charge for it. While this approach may make some sense from an industrial and intellectual property policy perspective, it appears to conflict with recent Supreme Court jurisprudence on the nature and purpose of the PMPRB. According to the Supreme Court, the PMPRB’s mandate is to “balance the monopoly power held by the patentee of a medicine, with the interests of purchasers of those medicines” Footnote 5. The Supreme Court further found that the PMPRB, in interpreting its consumer protection mandate, must take into paramount account its responsibility for ensuring that patentees do not abuse their statutory monopolies “to the financial detriment of Canadian patients and their insurers.”

Whereas patents exist to reward innovation through the exclusive rights they confer on patentees, the PMPRB exists to ensure that patentees do not abuse those rights by charging consumers excessive prices during the statutory monopoly period, in the same way that compulsory licensing sought to achieve price containment through competition in the marketplace.Footnote 6 Put another way, the PMPRB does not embody a balance between two competing federal policy objectives; rather, it acts as one half of that balance by serving as a counterweight to and reasonable check on the exclusive rights afforded to pharmaceutical patentees.

As a sector-specific regulator charged with a form of oversight over how a particular type of patentee – one that is entitled to the benefit of a patent for an invention that pertains to a medicine – exercises those rights, the PMPRB can be distinguished from other pharmaceutical regulatory bodies in Canada, such as the Institut national d’excellence en santé et en services sociaux (INESSS) in Quebec, and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) in the rest of Canada, whose principal function is to conduct economic evaluations of new drugs based on their therapeutic merits relative to existing therapies.

An approach toward categorizing new patented drugs that could be more in keeping with the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the PMPRB’s purpose and its unique regulatory role within the Canadian system would be to conduct an initial screening based on indicators of potential for abuse of statutory monopoly, rather than clinical evidence of therapeutic superiority. Such an approach would apply indicators that are rationally and directly connected to the statutory factors as the starting point in the analysis of whether a drug might be priced excessively, rather than an ancillary step to an assessment of degree of therapeutic improvement, which is not explicitly contemplated in the Act and duplicates the work of both CADTH and INESSS. For example, a drug with an introductory price in Canada in excess of a pre-established threshold or that is likely to cause rationing by public and private drug plans based on cost or projected usage, could attract greater regulatory scrutiny in terms of the setting of a ceiling price. The same approach could apply to a drug with few, if any, competitors in its therapeutic class, however that class may be defined. Therapeutic benefit could still be taken into account in this context, but as an indicator that greater regulatory oversight may be warranted, as opposed to licence to charge a premium price.

There is evidence that the ability of pharmaceutical patentees to charge high prices has been increasing in recent years. Higher industry concentration due to mergers and acquisitions as well as greater specialization of the R&D pipeline contribute to this observation in Canada: four pharmaceutical companies account for more than 65% of all revenues in 9 of 10 of the largest pharmaceutical subgroupsFootnote 7 (65% of revenues controlled by 4 or fewer firms is generally recognized as a high risk to consumers). By an alternative metric (the Hirschman-Herfindahl Index), 7 of the largest 10 pharmacological subgroups have scores above 2500 (the threshold for determining a high risk to consumers). At the firm-specific level, in 2014, Canadian pharmaceutical patentees derived 58% of their revenue, on average, from a single pharmacological subgroup, as compared to 47% in 2007.

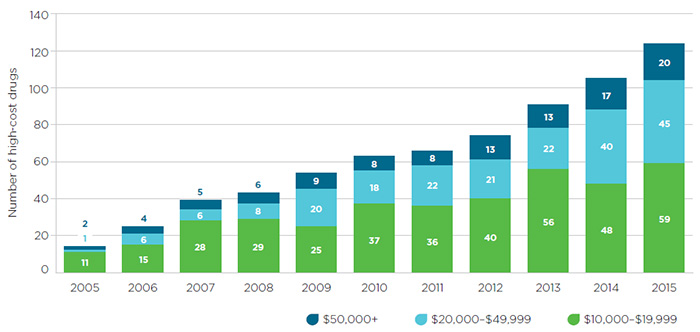

The potential for high pricing brought about by market concentration is compounded by the increasing industry focus on the development of high-cost specialty drugs, as mentioned earlier. Global spending on these drugs is projected to quadruple by 2020. In 2014, Canadian spending on biologics and oncology drugs grew by double digits and spending on new medicines alone increased tenfold, due mainly to very high priced treatments for Hepatitis C. The growing number of high-cost drugs entering the Canadian market over the last decade is reflected in Figure 1 (where “high-cost” is defined as a drug for which private insurance plans pay more than $50,000 annually per beneficiary).Footnote 8

Figure 1 – Sales of high-cost drugs in Canada since 2005

Source: IMS Brogan Pay-Direct Private Drug database, 2005-2014, IMS AG. All rights reserved.

Figure description

This segmented bar graph depicts the number of high-cost drugs entering the Canadian market each year from 2005 to 2015. Each bar is divided into three sections, with each representing an annual drug cost range: $10,000 to $19,999; $20,000 to $49,999; and $50,000 or more.

The number of drugs in all three groups increased over the 10-year time period:

- $10,000 to $19,999: 11 drugs in 2005 and 59 in 2015.

- $20,000 to $49,999: 1 drug in 2005 and 45 in 2015.

- $50,000 or more: 2 drugs in 2005 and 20 drugs in 2015.

The impact of this trend has been particularly striking in the private insurance market, where spending on drugs that exceed $50,000 annually has grown from 1% of total Canadian spending on patented drugs in 2005 to 7.4% in 2015.Footnote 9 Similarly, whereas in 2005, an average private drug plan of 100,000 active beneficiaries included only 3 beneficiaries with $50,000 or more in annual drug costs, this number had increased to 48 by 2015. There has also been a notable increase in the number of private drug plan beneficiaries with annual drug costs ranging from $20,000 to $49,999. While these patients accounted for 4.2% of total drug plan costs in 2005, by 2015 their share had increased to 13.9%.

These trends all point to the need for greater coordination and collaboration among regulators at the federal, provincial and territorial levels, but also between payers of all stripes in both the public and private market.

Despite the Supreme Court’s reasoning and the changes in the pharmaceutical marketplace described previously, the PMPRB’s current approach to categorizing medicines by therapeutic benefit is not geared to questions of market dynamics, high prices or affordability. This results in undue regulatory burden on patentees and frustrates the ability of the PMPRB to prioritize its enforcement resources on cases where payers are most in need of regulatory relief.

International price comparisons

Most developed countries engage in some form of international price comparison to limit drug costs, although increasingly as an adjunct to other forms of cost containment because of the worldwide practice of confidential discounts and rebates and the concomitant unreliability of public list prices. The PMPRB’s longstanding benchmark for determining whether it is carrying out its mandate effectively is that, on average, Canadian prices should not exceed median PMPRB7 prices. This target appears to have arisen from the notion that Canadians should not pay more than their “fair share” of the international costs related to the R&D of new medicines.

Although Canadian prices remain slightly below median prices in the PMPRB7, this is due to the fact that US prices, which are much higher on average than all other PMPRB7 countries, skew the median calculation. This gap has increased markedly in recent years, with US prices on average 60% higher than Canadian prices in 2000, but 247% higher by 2014.Footnote 10 As it stands, of the many developed countries that engage in international price referencing, only Canada and South Korea currently benchmark against US prices.

The policy rationale for practicing international price referencing is to establish the range of prices that pharmaceutical companies find acceptable in exchange for their medicines. International price referencing can be revealing both of what a company is willing to accept, and, conversely, the maximum that it can reasonably expect to be paid. However, the current reality is that the actual prices being paid in European countries are below the public prices that the PMPRB is constrained to use for international comparison purposes. Furthermore, while the current PMPRB Guidelines set price ceilings based on highest and median international prices, depending on the drug’s perceived therapeutic benefit, other countries are much more restrictive. Switzerland, for instance, requires prices to be below the average of a set of mid- to low-priced countries.

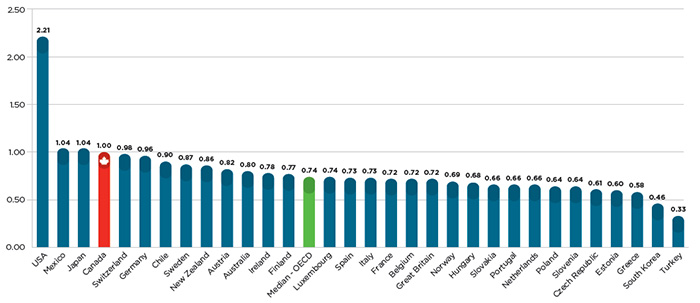

Given all of the above, it is perhaps not surprising that Canadians pay among the highest patented drug prices in the world, as illustrated by Figure 2, which shows that Canadian prices were 35% higher than the OECD average for the same drugs in 2014.

Figure 2 – Average foreign-to-Canadian price ratios in 2014

Source: IMS MIDAS™ database, 2005-2014, IMS AG. All rights reserved.

Figure description

This bar graph gives the 2014 average foreign-to-Canadian price ratios for individual countries belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), as well as the OECD median value.

| USA |

2.21 |

| Mexico |

1.04 |

| Japan |

1.04 |

| Canada |

1.00 |

| Switzerland |

0.98 |

| Germany |

0.96 |

| Chile |

0.90 |

| Sweden |

0.87 |

| New Zealand |

0.86 |

| Austria |

0.82 |

| Australia |

0.80 |

| Ireland |

0.78 |

| Finland |

0.77 |

| Median - OECD |

0.74 |

| Luxembourg |

0.74 |

| Spain |

0.73 |

| Italy |

0.73 |

| France |

0.72 |

| Belgium |

0.72 |

| Great Britain |

0.72 |

| Norway |

0.69 |

| Hungary |

0.68 |

| Slovakia |

0.66 |

| Portugal |

0.66 |

| Netherlands |

0.66 |

| Poland |

0.64 |

| Slovenia |

0.64 |

| Czech Republic |

0.61 |

| Estonia |

0.60 |

| Greece |

0.58 |

| South Korea |

0.46 |

| Turkey |

0.33 |

To put this differential in perspective, there were $13.7 billion in sales of patented medicine products in Canada in 2014. If Canadians paid the OECD average for these medicines, consumers would have saved nearly $3.6 billion, of which $2.8 billion would have been split evenly between public and private insurance plans, and $800 million returned directly to individual households.

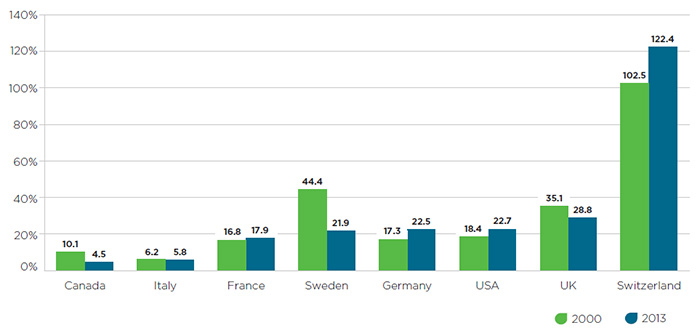

As drug prices in Canada rise relative to international comparators, pharmaceutical R&D investment in this country has been in steady decline.

Figure 3 – R&D-to-sales ratios in 2000 and 2013

Figure description

This bar graph gives the research-and-development-to-sales ratios for Canada and the seven PMPRB comparator countries for 2000 and 2013. The values are as follows:

| Country |

2000 |

2013 |

| Canada |

10.1% |

4.5% |

| Italy |

6.2% |

5.8% |

| France |

16.8% |

17.9% |

| Sweden |

44.4% |

21.9% |

| Germany |

17.3% |

22.5% |

| United States |

18.4% |

22.7% |

| United Kingdom |

35.1% |

28.8% |

| Switzerland |

102.5% |

122.4% |

In general, R&D investment in recent years has been increasingly concentrated in countries that host multinational headquarters of major pharmaceutical firms, such as Germany, the US, and Switzerland. With the wisdom of hindsight comes the realization that Canada’s approach of benchmarking prices against countries with R&D levels it sought to emulate is based on a flawed policy presumption. In light of this fact and the artificially inflated public list prices in these countries, there is an argument to be made that either the composition of the PMPRB7 should change so as to better align with Canada’s present-day R&D levels and key economic and health system indicators, or the manner in which the Guidelines set price ceilings relative to the PMPRB7 should be revised downward to align with the more restrictive approach taken in countries such as Switzerland.

Domestic price comparisons

Under the current Guidelines, new patented drugs that fall into the “slight or no improvement” category are permitted to price at the top of the domestic therapeutic class. This is problematic for two reasons. First, it is out of step with the way many other countries regulate the pricing and reimbursement of so-called “me-too” drugs, leading to a significant price gap for this category of drugs between Canadian and median PMPRB7 prices.Footnote 11 Second, as is the case with international comparisons, the prices upon which the PMPRB relies for domestic comparison purposes do not reflect the confidential discounts and rebates patentees routinely provide to their largest paying customers. The impact of confidential pricing is perhaps most pernicious in this category given that it accounts for over 80% of drugs under PMPRB jurisdiction.

Price transparency is an issue with which all developed countries grapple, and will undoubtedly require international cooperation if a solution is to be found. However, potential changes to the Guidelines may assist in mitigating the impact of the lack of price transparency by lowering price ceilings as a proxy for the true price net of rebates and discounts. If the goal of therapeutic class comparison is to protect Canadians from the risk that new patented medicines will raise treatment costs to excessive levels, then referencing the highest price in a therapeutic group pushes price ceilings in the wrong direction. Only if therapeutic class comparisons occur with reference to some measure of class centrality (such as average or median prices) or minimality (such as lowest prices) would the upward drift in prices resulting from the introduction of successive me-too drugs be held in check.Footnote 12

At the same time, the fact that me-too drugs with multiple domestic therapeutic comparators face some measure of competition, however imperfect (the market for prescription drugs is unique in that those who choose do not pay, and those who pay do not chose), may argue in favour of less regulatory oversight of this class of drugs, not more. One solution to these competing considerations would be to introduce lower price ceilings for me-too drugs in the Guidelines at introduction, but take a more relaxed approach to monitoring them on a go-forward basis having regard to the lower risk of excessive pricing. This approach would allow for a more strategic and targeted use of the PMPRB’s resources while preserving the potential exercise of its jurisdiction over all patented medicines.

Price increases based on changes in the Consumer Price Index

Every country has an interest in ensuring that pharmaceutical prices are stable and predictable over time. In Canada, this is reflected in the Act and Guidelines to the extent that patented drug prices cannot increase by more than average inflation (as measured by CPI) in a given year. However, other countries, such as France, Sweden and Switzerland, take a more stringent approach in that pharmaceutical prices either cannot increase or must decrease at specified intervals. This makes sense given that, over time, both the marginal cost of producing a drug should be expected to decrease and price competition from subsequent drugs is felt in the market. Policies which normalize such expectations stand out as good examples of consumer protection.

The policy rationale for considering Canadian patented pharmaceutical prices in the context of changes in the CPI is to prevent the price of any given medicine from increasing at a greater rate than the average price level for all goods and services sold in Canada (for which the CPI is a well-established proxy). This is linked to the PMPRB’s consumer protection role: if pharmaceutical patentees are able to raise prices for their goods at a greater rate than those of other goods and services, this could be an indicator of excessive pricing.

The current PMPRB practice in this regard is generally seen as achieving its goals: the average rate of change for patented pharmaceutical prices in Canada has been less than CPI since 1992. However, this approach masks serious concerns at a higher level, most notably that, with the exception of the US, the pharmaceutical price regulatory systems in other countries have a bias towards decreasing prices. For example, between 2008 and 2014, the prices of 64% of patented medicines sold in both Canada and Switzerland decreased in Switzerland but increased in Canada.Footnote 13 This pattern is similar among the other non-US PMPRB7 comparators.

Furthermore, the PMPRB practice of reviewing all patented medicines annually relative to CPI and against the highest international price, but only once (at introduction) relative to therapeutic category, is out of step with the approach in many other countries. For instance, Switzerland completely reassesses the prices of one-third of prescription medicines every year (such that the entire portfolio is reassessed every three years). France reassesses medicines at a minimum of 2 years, and a maximum of 5 years, depending on whether additional clinical or observational data have been developed. Although the Act clearly contemplates that CPI should be considered by the PMPRB in seeking to determine whether a patented drug has become excessively priced, this does not preclude the PMPRB from considering it in a different manner than currently prescribed under the Guidelines, provided it is equally reasonable, or providing for the periodic reassessment of drug prices to determine, based on other section 85 factors, whether a decrease may be warranted. This could be the case where, for example, following the PMPRB’s review of a new drug’s introductory price, it is approved or prescribed for additional indications, such that the class of drugs it should be compared to for pricing purposes has changed or its affordability profile for payers is significantly impacted.

Any market price review

As mentioned, the lack of price transparency in the Canadian pharmaceutical system allows patentees to discriminate between different classes of consumers. The Act empowers the PMPRB to evaluate whether the price of a patented medicine is excessive “in any market” in Canada. The current Guidelines give effect to this authority by scrutinizing prices at the wholesaler, pharmacy and hospital levels and in each province and territory. However, this is only done at introduction. In subsequent years, “any market” reviews only take place if a medicine is already under investigation.

According to the data that patentees file with the PMPRB (in which they must provide average price data at the provincial level), if consumers in all provinces had access to the price that consumers in the lowest priced province pay, total Canadian spending on patented pharmaceuticals would decrease by more than $600 million – an overall reduction of almost 5%.

Given that the Act contemplates an assessment of price in “any market”, consideration of equity between customer classes, whether by region or payer type, could play a more prominent role in determining whether the price of a patented medicine is excessive.

Towards a modernized framework

As mentioned, recent and significant changes in the PMPRB’s operating environment necessitate corresponding changes to modernize and simplify its regulatory framework. It is recognized that there will be competing views from stakeholders and the public on this point and that consensus is unlikely to emerge from consultations on a singular set of changes that all parties believe are warranted under the circumstances. This is to be expected given the intersecting and conflicting political, economic, social, legal, commercial and technological issues and interests at play. This paper is not intended to provide an exhaustive treatment of the case for change and what form it might take. That is precisely the point of consultations and the PMPRB looks forward to engaging in a comprehensive, nationwide dialogue with its stakeholders and the public in the coming months to ensure that all voices are heard and no stone is left unturned.

Questions for Discussion

As a first step in giving effect to its duty to consult under section 96(5) of the Act, the PMPRB is asking the following series of questions designed to initiate the discussion on Guidelines modernization. The feedback received in response to these questions will inform the initial phase of the PMPRB’s consultations process, as explained previously under the “What are we doing?” section of the paper.

- What does the word “excessive” mean to you when you think about drug pricing in Canada today? For example:

- Should a drug that costs more annually than a certain agreed upon economic metric be considered potentially excessively priced?

- Should a drug that costs exponentially more than other drugs that treat the same disease be considered potentially excessive?

- In considering the above two questions, does it matter to you if a very costly drug only treats a small group of patients such that it accounts for a very small proportion of overall spending on drugs in Canada?

- Conversely, if a drug’s price is below an agreed upon metric and in line with other drugs that treat the same disease, should it be considered potentially excessive if it accounts for a disproportionate amount of overall spending on drugs in Canada?

- What economic considerations should inform a determination of whether a drug is potentially excessively priced?

- Given that it is standard industry practice worldwide to insist that public prices not reflect discounts and rebates, should the PMPRB generally place less weight on international public list prices when determining the non-excessive price ceiling for a drug?

- In your view, given today’s pharmaceutical operating environment, is there a particular s. 85 factor that the Guidelines should prioritize or weigh more heavily in examining whether a drug is potentially excessively priced?

- Should the PMPRB set its excessive price ceilings at the low, medium or high end of the PMPRB7 countries (i.e., the US, the UK, Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, France and Italy)?

- Does the amount of research and development that the pharmaceutical industry conducts in Canada relative to these other countries impact your answer to the above question and if so, why?

- What alternatives to the current approach to categorizing new patented medicines (based on degree of therapeutic benefit) could be used to apply the statutory factors from the outset and address questions of high relative prices, market dynamics and affordability?

- Should the PMPRB consider different levels of regulatory oversight for patented drugs based on indicators of risk of potential for excessive pricing?

- Should the price ceiling of a patented drug be revised with the passage of time and, if so, how often, in what circumstances and how much?

- Should price discrimination between provinces/territories and payer types be considered a form of excessive pricing and, if so, in what circumstances?

- Are there other aspects of the Guidelines not mentioned in this paper that warrant reform in light of changes in the PMPRB’s operating environment?

- Should the changes that are made to the Guidelines as a result of this consultation process apply to all patented drugs or just ones that are introduced subsequent to the changes?

- Should one or more of the issues identified in this paper also or alternatively be addressed through change at the level of regulation or legislation?

Instructions for submitting comments

Written comments must be submitted by e-mail, letter mail or fax by October 24, 2016 to:

Patented Medicine Prices Review Board

(Rethinking the Guidelines)

Box L40, 333 Laurier Avenue West, Suite 1400

Ottawa, Ontario K1P 1C1

Fax: 613-952-7626

E-mail: PMPRB.Consultations.CEPMB@pmprb-cepmb.gc.ca

Appendix 1: Strategic Plan 2015-2018

In 2014, the PMPRB initiated a year-long strategic planning process culminating in the publication of the Strategic Plan 2015-2018. This plan will inform the work of the PMPRB going forward over the next few years and reflects the vision as to how the PMPRB can best leverage its strengths and unique legislative remit to complement the efforts of its federal, provincial and territorial partners and other stakeholders in advancing the common goal of a sustainable health system. The full Strategic Plan 2015-2018 document is available on the PMPRB website.